Recognizing

ATTR‑CM

Learn about this unrelenting, progressive heart disease

ATTR‑CM can diminish quality of life, cause recurrent hospitalization, and lead to premature death.1

ATTR-CM Diagnosis

Early diagnosis enables early interventions that may help slow disease progression.2-4 A noninvasive diagnostic algorithm is available to facilitate timely identification of patients with ATTR-CM.5

Delayed diagnosis prevents timely intervention and contributes to premature death.1,2,6

>4 years median diagnostic delay1

3–5 years median survival1

in untreated patients following diagnosis

Although ATTR‑CM has become an increasingly recognized cause of heart failure and arrhythmia, misdiagnosis is common.4,6

Patient Populations Considered At-Risk for ATTR‑CM3

ATTR‑CM Red Flags

Recognizing these cardiac and extracardiac manifestations of ATTR‑CM can lead to early diagnosis2

Transthyretin (TTR) amyloid fibrils can accumulate both within and outside of the heart, leading to diverse signs and symptoms.2

Potential Signs of Amyloid Fibril Accumulation

Within the Heart

Echocardiogram (ECG)

- Reduction in longitudinal strain with apical sparing3

- Discrepancy between left ventricular (LV) thickness and QRS voltage3

- Atrioventricular block in the presence of increased LV wall thickness3

- Hypertrophic phenotype with associated infiltrative features3

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR)

- Marked extracellular volume (ECV) expansion, abnormal nulling time for the myocardium, or diffuse late gadolinium enhancement3

Therapeutic response

- Intolerance to standard heart failure therapies (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta blockers)2

Biomarkers

- Mild increase in troponin levels on repeated occasions3

Potential Signs of Amyloid Fibril Accumulation Outside of the Heart

Neuropathic

- Symptoms of polyneuropathy and/or dysautonomia3

Orthopedic

- History of bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome3

- Lumbar spinal stenosis2

- Spontaneous rupture of the distal biceps tendon2

Ocular

- Vitreous involvement, such as abnormal blood vessel formation, dark floaters, pupillary abnormalities, and/or dry eye7

Renal

- Renal impairment and proteinuria8

Gastrointestinal

- Chronic diarrhea or diarrhea alternating with constipation, often with an absence of abdominal pain8

ATTR-CM Subtypes

There are 2 subtypes of ATTR-CM2:

- Wild-type (ATTRwt-CM) comes from age-related changes to the TTR protein

- Variant (ATTRv-CM) occurs through variants in the TTR gene*

*Also known as hereditary ATTR-CM (ATTRh-CM).

80% of patients9

20%9†

Wild-type ATTR-CM2,8,10

- Sporadic disease

- TTR gene has normal sequence; TTR protein becomes unstable with age

- Reduced symptom severity at diagnosis

- Typically manifests later in life (70-75 years of age)

Variant ATTR-CM1,10,11

- Autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance

- Variant sequence in TTR gene destabilizes the TTR protein

- More severe disease at diagnosis (poorer survival, EF, renal function, and performance status)

- Typical age of onset is >60 years of age

†In a study of 879 people with ATTR-CM.9

A prevalent pathogenic TTR gene variant is V122I, which affects 3%-4% of all Black Americans and has been found in 10% of those aged 65 years or older with severe congestive heart failure12

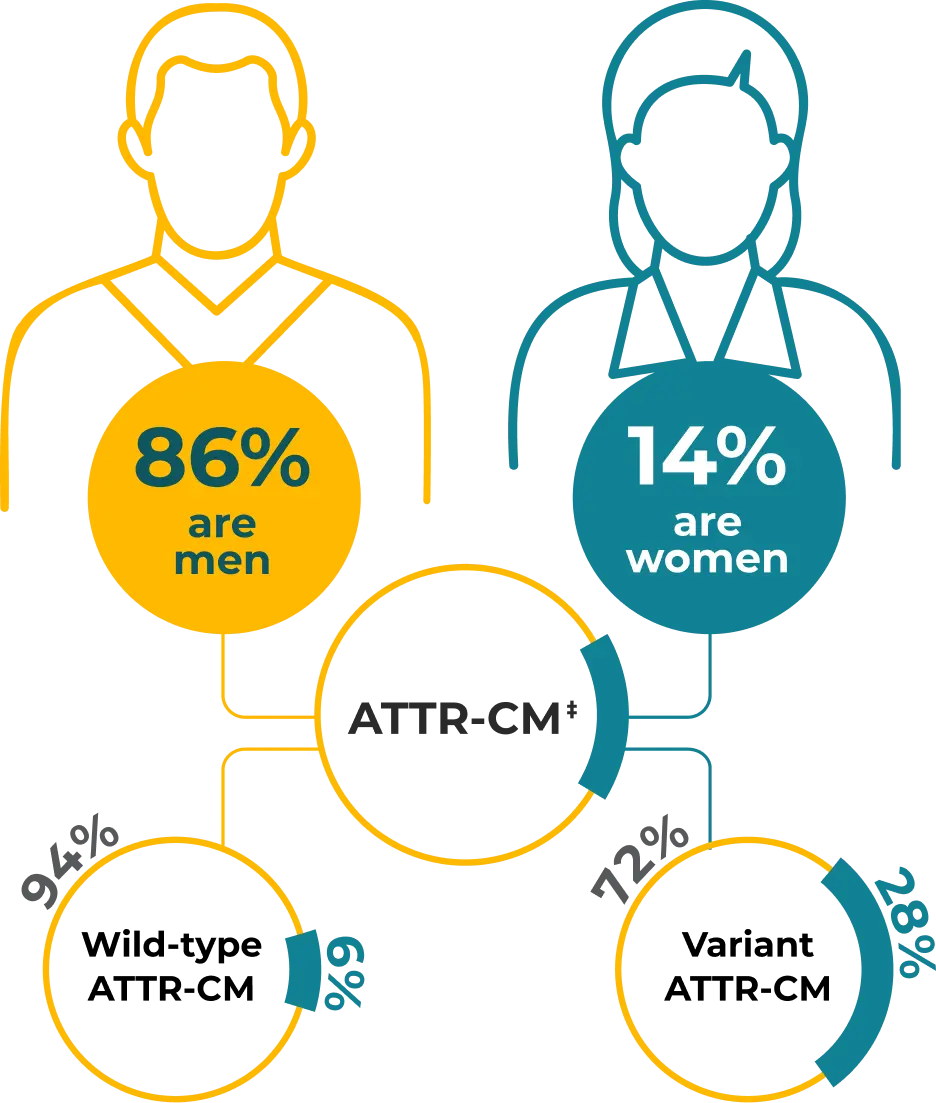

Sex Differences in ATTR‑CM

Although predominantly diagnosed in men, ATTR-CM is becoming increasingly recognized in women13

‡In a study of 1732 consecutive patients, comprising 1095 with wild-type ATTR-CM and 637 with variant ATTR-CM.13

Lane T, Fontana M, Martinez-Naharro A, et al. Natural history, quality of life, and outcome in cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2019;140(1):16-26. 2. Rozenbaum MH, Large S, Bhambri R, et al. Impact of delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM): a targeted literature review. Cardiol Ther. 2021;10(1):141-159. 3. Kittleson MM, Maurer MS, Ambardekar AV, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis: evolving diagnosis and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(1):e7-e22. 4. Griffin JM, Rosenthal JL, Grodin JL, Maurer MS, Grogan M, Cheng RK. ATTR amyloidosis: current and emerging management strategies: JACC: CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3(4):488-505. 5. Witteles RM, Bokhari S, Damy T, et al. Screening for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in everyday practice. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(8): 709-716. 6. Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, et al. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016;133(24): 2404-2412. 7. Gertz M, Adams D, Ando Y, et al. Avoiding misdiagnosis: expert consensus recommendations for the suspicion and diagnosis of transthyretin amyloidosis for the general practitioner. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):198. 8. Reynolds MM, Veverka KK, Gertz MA, et al. Ocular manifestations of familial transthyretin amyloidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:156-162. 9. Law S, Bezard M, Petrie A, et al. Characteristics and natural history of early-stage cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(27):2622-2632. 10. Ruberg FL, Grogan M, Hanna M, Kelly JW, Maurer MS. Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(22):2872-2891. 11. Michels da Silva D, Langer H, Graf T. Inflammatory and molecular pathways in heart failure-ischemia, HFpEF and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2322. 12. Buxbaum JN, Ruberg FL. Transthyretin V122I (pV142I)* cardiac amyloidosis: an age-dependent autosomal dominant cardiomyopathy too common to be overlooked as a cause of significant heart disease in elderly African Americans. Genet Med. 2017;19(7):733-742. 13. Patel RK, Ioannou A, Razvi Y, et al. Sex differences among patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy – from diagnosis to prognosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(12):2355-2363.

The information provided on this site is intended for use by healthcare professionals practicing in the United States.

By clicking ENTER you confirm you are a healthcare professional practicing in the United States.

Thank you for visiting TTRMatters.com

If you are a healthcare provider and want to learn more about an ATTR-CM treatment option, click "Continue."

To remain on TTRMatters.com, click "Stay."